Hubert Robert, French artist, born in Paris. (May 22, 1733 – April 15, 1808)

Hubert Robert spent eleven years in Rome; after the young artist's official residence at the French Academy in Rome ran out, he supported himself by works he produced for visiting connoisseurs like the abbé de Saint-Non, who took Robert to Naples in April 1760 to visit the ruins of Pompeii. The marquis de Marigny, director of the Bâtiments du Roi kept abreast of his development in correspondence with Natoire, director of the French Academy, who urged the pensionnaires to sketch out-of-doors, from nature: Robert needed no urging; drawings from his sketchbooks document his travels: Villa d'Este, Caprarola. Robert spent his time in the company of young artists in the circle of Piranesi, whose capricci of romantically overgrown ruins influenced him so greatly that he gained the nickname Robert des ruines.The albums of sketches and drawings he assembled in Rome supplied him with motifs that he worked into paintings throughout his career.

His success on his return to Paris in 1765 was rapid: the following year he was received by the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, with a Roman capriccio, The Port of Rome, ornamented with different Monuments of Architecture, Ancient and Modern. During the Revolution, he was arrested in October 1793. He survived his detentions at Sainte-Pélagie and Saint-Lazare, by painting vignettes of prison life on plates, before he was freed at the fall of Robespierre.Robert narrowly escaped the guillotine when through error another prisoner died in his place. Subsequently he was placed on the committee of five in charge of the new national museum at the Palais du Louvre.

Le Pont Sur Le Torrent, painted in the mid-1780s by Hubert Robert, measures over 20 feet wide by 13 feet high, and carries an estimate of $2 million - $3 million. Originally commissioned by the Duc de Luynes for the dining room of his mansion in Paris, in 1925 it was acquired at auction by William Randolph Hearst and once decorated the beachfront castle that the newspaper baron purchased in late 1927 in Sands Point, Long Island as a retreat for his wife Millicent. The awe-inspiring artwork has not been seen in public in more than 50 years.

Artist: Hubert Robert Title: The Bridge Confiscated Collection: Sel 169 (previously Sel 156) (Seligmann, Paris)

This work was seized by the Nazis from Edouard Alphonse James de Rothschild. In 1940, the Baron and his wife escaped to Lisbon, Portugal right after the Nazi occupation of France. From there they were able to continue on their way to New York City, New York. It is there that they waited until the end of World War II to return to their homeland of Austria. But before his escape to the United States, James and his wife did their best to hide their massive art collection worth millions from the Nazi's. He hid most of his collection somewhere on the Haras de Meautry farm and at his Château de Reux estate. But in 1940, the Nazi's caught up with the Rothschild's treasure, raiding and looting everything in sight.

In this image Hubert Robert draws a rare view of Paris and depicts its most iconic building, the cathedral of Notre Dame. It is shown from the unusual angle beneath the Pont au double also known as the Pont de l'Hôtel Dieu (replaced in 1883 with the current bridge). The cathedral is seen from the east with its two Gothic towers and flying buttresses. The imposing monumentality of the cathedral is tempered by the bridge which takes up nearly half the sheet. The main protagonists, the three fishermen in the lower left corner, while diminutive in comparison to the architecture do not fail to capture the viewer's eye either.

Strangely, and perhaps tellingly, Robert chose to emphasize the bridge rather than the Gothic church. Bridges, real or imagined were a frequent motif in Robert's oeuvre. Two paintings by him depict the transformation of two bridges in Paris: The demolition of houses on the Pont Notre-Dame in 1786 (Karlsruhe, Staatliche Kunsthalle), and The demolition of houses on the Pont-au-Change in 1788 (Paris, Musée Carnavalet).

For a full discussion of bridges in Robert's work see Hubert Robert 1733-1808 und die Brücken von Paris (exhib. cat., Karlsruhe, Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe, 1991).

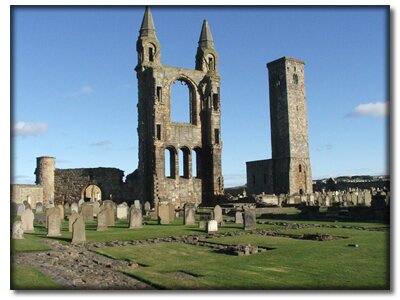

Take a walk on the moors, go horseback riding on ancient trails, or tour a medieval village in one of the U.K.'s 15 national parks. Known as "Britain's breathing spaces," the parks offer outdoor and sightseeing activities against dramatic landscapes and historic treasures.

Take a walk on the moors, go horseback riding on ancient trails, or tour a medieval village in one of the U.K.'s 15 national parks. Known as "Britain's breathing spaces," the parks offer outdoor and sightseeing activities against dramatic landscapes and historic treasures.